HEAD-QUARTERS DISTRICT OF TEXAS

Galveston, Texas, June 19, 1865

General Orders

No. 3

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a Proclamation from the

Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality

of rights, and rights of property between former master and slaves and the connec-

tion heretofore existing between them becomes that of employer and free laborer.

The freedmen are advised to remain at their present homes and work for wages. They

are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at Military Posts, and that they

will not be supported in idleness, there or elsewhere.

by Order of G. Granger, Major General Commanding

F.W. Emory, Major and A.A. Gen’l

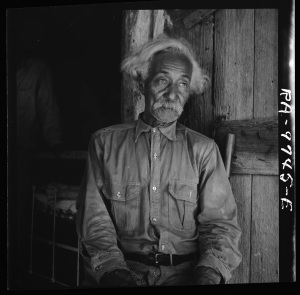

Today is the 150th anniversary of Juneteenth, the name that has become associated with the liberation of slaves in Texas at the end of the Civil War. Texas, as the western-most state of the Confederacy, was largely spared the presence of federal troops until the end of the war. Indeed, it became a common practice of slaveholders from outside Texas to “refugee” their slaves there in an ultimately vain effort to prevent their liberation.

Remembering this event would be of little importance outside of Texas except that in recent decades June 19 has become something an unofficial date to remember and celebrate nationwide the end of slavery in the United States. Why exactly, I am frankly not sure. But in essence, it is appropriate because Juneteenth represents an ad hoc commemoration of what was a largely ad hoc event. That is, while there are numerous milestones during the Civil War in slavery’s demise, for most slaves their liberation, that is the moment when they could finally effectively be free in practice, occurred incrementally throughout the war and its aftermath. Indeed, stories abound (likely apocryphal) of slaveholders on isolated plantations trying to keep the news of the end of slavery from their chattel.

But it is important to remember that even the liberation of slaves in Texas on June 19, 1865 that slavery was not completely dead yet in the United States, legally or practically. Legally, slavery had still not ended yet in Kentucky or Delaware which, thanks to their status as loyal slave states, were exempt from the Emancipation Proclamation (which interestingly was the authority cited by Union occupation authorities in Texas in June 1865 to order freedom for the state’s slaves). Kentucky slaveholders in particular, many Unionists, stubbornly held on to their human property in the belief that their loyalty during the war should somehow exempt them from any sort of emancipation. Indeed, slavery in those two states would not come to an end until final ratification of the 13th Amendment in December 1865.

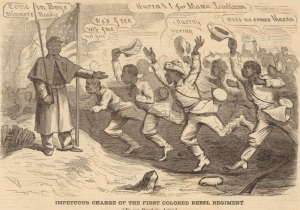

So while Juneteenth is a convenient day to celebrate the end of slavery in the United States, it is important to recognize that nearly any day of the year would be equally appropriate. An important reason for this fact is that African Americans played an active role in their own liberation. While the so-called “self-emancipation” thesis can be rejected as overly simplistic, and even many of the scholars identified with it are not so simple-minded as to believe the slaves brought down slavery all by themselves, it is equally naive to believe slavery ended by the fiat of some governmental authority, whether it be Abraham Lincoln or Gen. Gordon Granger, who issued the now famous General Order No. 3, enforcing the Emancipation Proclamation in Texas. Emancipation was a process, in which many slaves were prime movers in their own liberation, whether it be by fleeing to Union lines, joining the federal army, giving information to Union troops, working more slowly in the fields, or in myriad other ways. In that process, the Union Army, northern politicians, humanitarians, etc. also played notable roles.

So celebrate emancipation on Juneteenth. But feel free to celebrate it any other day, and in any fashion you feel appropriate. And honor the spirit of emancipation in your daily lives, for that is the most meaningful way of all to commemorate the end of slavery in the United States.